The decade of the 1830s opened with the Second French Revolution, or the July Revolution. By 1834 slavery was abolished in the British Empire, and Charles Darwin aboard the HMS Beagle, anchored at the recently British-acquired Falkland Islands for the first time. Closer to home, the first half of the 1830s saw the outbreak of the ‘Tithe War’ in reaction to the enforcement of contributions on the Roman Catholic majority for the upkeep of the established state church, the Church of Ireland. In addition, 1834 saw the establishment of the National Education Act in Ireland and St Vincent’s Hospital was founded in Stephen’s Green, Dublin. Ireland saw modern advancements, as the first public railway in the country opened in December 1834, the Dublin and Kingstown Railway. As a wave of revolutions swept through Europe, and the tides of change were in motion with social reform and technological advancement, a more literal tide off the Waterford coast revealed one of rarest birds in the world, a sighting and eventual capture which would become the last recording of a creature that had graced our shores since prehistoric times.

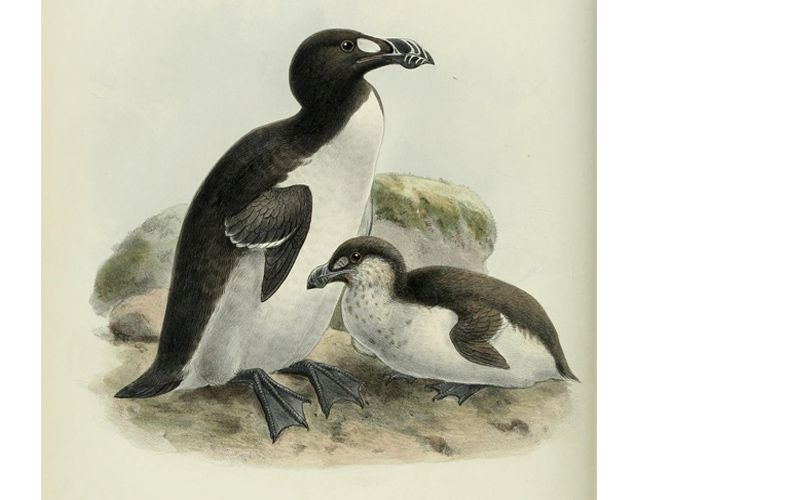

The Great Auk, with the Latin namesake pinguinus impennis and the Irish name falcóg mhór meaning ‘big seabird’ was a large relation to the Razorbill, Guillemot and Puffin. Although not a relation to the penguin, due to the Great Auk’s similarity being a black and white flightless seabird which stood as tall as a toddler and walked upright, when the penguin was discovered by Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in the fifteenth century, it was named after the Great Auk, or pinguinus impennis. Once numbering in millions, Great Auks were present as far south as Spain, but due to being hunted by man have been extinct since 1844. As the Great Auk was a flightless seabird, and the only flightless bird found in the Northern Hemisphere, they were not nimble on land, so it was very easy to cut off a flocks escape route when they were ashore and club them to death. Great Auks were historically used for their meat, feathers, skins and oils. The last surviving Great Auks in the world were a pair of incubating birds off the coast of Iceland on Eldey Island. They were killed by fishermen in their nest in 1844, and their single egg was smashed by one of the fisherman’s boots, quite literally stamping this ancient bird out of existence forever.

The history of the Great Auk is a rich and diverse one with cave drawing depictions of the bird dating from 20,000 years ago existing in southern France. The Great Auk was an important part of many Native American cultures also, both as a food source and as a symbolic creature. Maritime Archaic people, a cultural group found along the Newfoundland coast, were buried with Great Auk bones. In fact, a 4,000-year-old burial site in Newfoundland contained no less than two hundred Great Auk beaks. Burial garb would have been made from Great Auk skins with the heads and beaks left attached for decoration to ceremonial clothing, suggesting the cultural significance of the Great Auk to Maritime Archaic people. As it began to become evident that the Great Auk was facing a rapid decline in numbers, conservation attempts were put in place to secure the birds future. As early as the sixteenth century the Great Auk received its first official protection, and in the 1790s Great Britain outlawed the killing of the species for its feathers. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, a petition was drafted to protect the Great Auk and in the 1770s the Nova Scotian government asked the parliament of Great Britain to ban the killing of auks except for fishermen being allowed to kill auks if their meat was used as bait. The petition was granted by Great Britain, with the punishment for killing the auks for their feathers or taking their eggs resulted in public flogging- an apt revenge for the Great Auk which had historically been clubbed to death by hunters!

The story of the Great Auk in Ireland had its final chapter on our Waterford coastline. In May 1834, the last Great Auk recorded in Ireland was spotted between Ballymacaw and Brownstown Head by a David Hardy. A fisherman named only as ‘Kirby’ was tasked with the mission of retrieving the bird from the water. He observed that the auk was half starved and managed to entice it to his boat by throwing sprats to it, and eventually catching it in his landing net. According to Richard Ussher and Robert Warren’s book dating from 1900, The Birds of Ireland, a Mr Francis Davis of Waterford purchased the bird ten days after it was captured whereby it was then sent to a Mr Jacob Goff of Horetown Co. Wexford. The bird, an immature female, was kept in captivity and lived for four months until just like that, a prehistoric resident of our shores became forever extinct on the island of Ireland.

Fortunately, however, all is not lost as that is not where the journey for Waterford’s Great Auk ended. The remains of the bird were preserved by a Dr. Robert Burkitt who was a general practitioner and amateur ornithologist, and some ten years later the bird was presented to the Zoological Museum at Trinity College Dublin and is still part of their extensive collection. Interestingly, the Board of Trinity College granted a ‘Great Auk Pension’ of fifty pounds (over €7,000 by today’s standards) a year on Dr. Burkitt for the rest of his life as a token of their gratitude for his endeavour to conserve one of the rarest birds in the world. The Waterford Great Auk is a member of an elite club being one of just seventy-eight stuffed Great Auks in existence. A preserved Great Auk bought in 1971 by the Icelandic Museum of Natural History for £9,000 placed it in the Guinness Book of Records as the most expensive bird ever sold!

The story of the last Great Auk of Ireland is not the only legacy of the bird locally. Archaeological evidence uncovers the ancient history of the bird in Waterford. Sheltered among the sand-dunes in Tramore is the remains of an extensive kitchen midden, a prehistoric cooking and dumping ground, where layers of oyster and cockle shells were found alongside the bones of red deer as well as seventeen bones belonging to Great Auks, which represents at least six individual birds. Most of these bones were sent to the Museum of Zoology at University of Cambridge. Evidentially, the Great Auk was being used for food by the first humans to settle in the Waterford area and a breeding space for the auks would have had to exist within the vicinity. A possible location may have been Keeragh Islands off County Wexford where the flat and low-lying island with no threat of predators such as foxes or rats would have proved ideal.

The Great Auk holds the grim title of being the only Irish bird to become completely extinct within historical times. The story of the Great Auk from a natural history perspective is one of tragedy and a reminder of the ever present often negative impact of human activity on the environment. In the case of the Great Auk, the years preceding the bird’s extinction saw its value dramatically increase due to its rarity, which eventually led to its complete demise. However, the legacy of the Great Auk lives on through cultural, artistic and archaeological references from cave drawings dating to prehistoric times, to the appearance of the Great Auk in Leopold Bloom’s dream in James Joyce’s Ulysses, to being proud residents of zoological collections in some of the most prestigious universities in the world. The odyssey of the Great Auk brings us on a journey from Newfoundland to Iceland and back to our Waterford coast where in May 1834 the last lonesome Great Auk of Ireland took her final voyage.