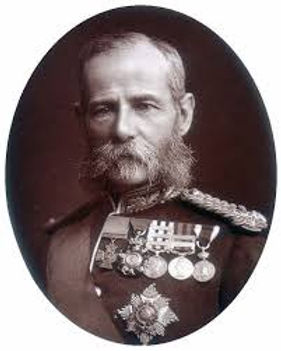

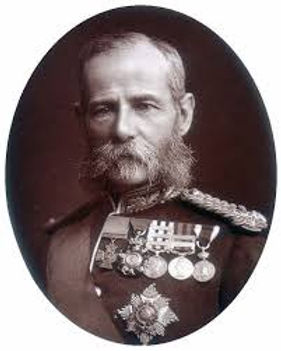

Many people in Waterford know the name of Field Marshal Lord Frederick Sleigh Roberts, the favourite of Queen Victoria – a brilliant soldier who earned a state funeral in 1914. However, while Roberts military successes were lauded at home, in the countries where he earned his medals he and the army carried out widespread atrocities in the name of Queen and Country. In a time where people all over the world are confronting the deeds and misdeeds of some of history’s best known figures, for today’s blog we have decided to look at a figure which has lately garnered some controversy: Roberts himself. The city has a complicated relationship with Roberts who was a source of great pride for the people of Waterford during his life, though in the modern world it is no wonder that he has attracted criticism. We often make the mistake in history of allowing black and white narratives to develop at the expense of a whole picture but Roberts was human, and as such was neither entirely evil nor utterly good a fact we have always stressed when asked about his bust on guided tours. Today then, we would like to provide a whole picture of a complex man who was adored by many but indisputably did great harm to many others, today we look at a life under the microscope.

Field Marshal Lord Frederick Roberts is perhaps the best known member of the Roberts family – a Waterford family of relatively new importance during his lifetime. He was a great grandson of the famous Waterford architect who designed the face of Georgian Waterford and sealed the fate of his family through a long and lauded career. John Roberts the architect was born into a middling Protestant family in Waterford in 1712 but as a young man he travelled to London to perfect his craft of architecture and allegedly eloped with a young Huguenot heiress named Mary Susannah Sautelle. On his return he quickly proved himself to be a rare talent and was contracted to finish the new Bishop’s Palace after Richard Cassels left the project. After proving himself on this building he built two more houses for the Bishop along with a number of other important buildings around Waterford such as the Assembly Rooms, the county and city infirmary and, highly unusually, both the Catholic and Church of Ireland cathedrals. Roberts and his wife had more than 20 children including the painter Thomas Roberts and in the following century their legacy included dozens of grandchildren scattered across Ireland, England and India. Roberts success helped to set up his family for generations to come and as one contemporary commentator pointed out, he possessed ‘the valuable qualities of integrity, thrift, industry and force of character, which ultimately led to prosperity and honour for himself and his descendants‘.

The home of John Roberts

Frederick Sleigh Roberts was born in India in 1832 to Sir Abraham Roberts and Isabella Bunbury. His father was a successful soldier who had been born in Waterford and the family spent a lot of time in the city when his father finally was allowed home from India during the 1840s. He was schooled initially in Eton to help him make connections that could help him as an adult before going on to Sandhurst and Addiscombe Military Seminary: “Freddy – is going to Eton – a most expensive seminary – but where he will meet the Sons of the first people of the Kingdom – which in after life is sometimes useful” – Frederick Robert’s uncle, Captain Thomas Roberts RN in 1844. He joined the East India Company Army with the help of his father on his graduation and became his Sir Abraham’s Aide de Camp in 1852.

General Sir Abraham Roberts

He seems to have developed a slightly conceited nature as a young man and when his cousin William wrote home from India in 1753 about the young soldier’s avoidance of him, his uncle Captain Thomas Roberts remarked: ‘I am not surprised to find that Fred had not paid you a visit, young chaps now a days are apt to think too much of themselves, particularly wearing epaulettes – but no matter & you were as well without his reacquaintance’. It seems then that very early on he showed a clear preference to his fellow military men, even above his own family. None-the-less, his connection to an extremely successful father and Abraham’s efforts to get his son the very best situation his connections could afford him ensured his own success early on.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857

He distinguished himself early in his career during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 for which he was awarded Britain’s highest award for gallantry – the Victoria Cross. He then fought in Abyssinia as well as Afghanistan and rapidly rose through the ranks, going from Captain to Quartermaster-General of the Bengal Army in just fifteen years. His actions in these countries though leave him less than distinguished by modern standards. While he was celebrated at home for the efficiency with which he put down insurrection in the colonies, in the countries which endured the often excessive force with which he did so, he is less fondly remembered. Like the rest of the British military at this time, Roberts sought to act decisively to establish and re-establish British rule in Afghanistan and Abyssinia, aiming to inflict as many casualties as possible on insurgents in order to stamp out resistance. In cases where casualties could not be inflicted they attempted to draw out the rebels by inflicting damage on the local economy through confiscating land and destroying livestock – a move which some historians have argued, only served to prolong war rather than to end it.None the less, his superiors were pleased with his strong policies and actions and rewarded him by making him Baron of Kandahar in Afghanistan and the City of Waterford.

He is possibly best known for his participation in the second Anglo-Boer War where he won the last victory of his career before retirement. His ruthlessness was apparent here too during the Siege of Kimberley when he assembled the largest British military force in history and told his officers:”You must relieve Kimberley if it costs you half your forces“. In one of the most controversial moves of his entire career, under Roberts white Afrikaner commandos were forced to submit to British rule using various methods, including concentration camps. The camps were devised as somewhere to place the families displaced by British destruction of property but conditions were abysmal and the death rate was extremely high due to heat, overcrowding, lack of supplies and disease. He was made an Earl for his actions in the Boer war, upgraded to the Earl of Kandahar and the City of Waterford.

Soldiers in the second Boer War

He later became the last Commander in Chief of the Forces of the British Empire and was knighted several times over the course of his long career. He was recalled from retirement at the outbreak of World War One and dispatched to the front to help rally the troops and provide motivation, where he became the oldest soldier to die in uniform after losing his battle with pneumonia at St, Omer, France, on November 14th 1914.

Known widely as ‘Bobs’ by his affectionate troops to whom he acted as a mascot as well as an understanding leader. While he was ruthless in battle he was intensely protective of the young soldiers under him when he could afford to be and this included young Indian soldiers as well as white British officers. Roberts was close to Queen Victoria and there is some speculation that the phrase ‘Bobs’ your Uncle’ could be related to him. After his death he became one of only two non-members of the royal family to lie in state in Westminster Hall (Winston Churchill being the second) and was given a state funeral. Today, Waterford has a complicated relationship with Roberts, because while his decisive military victories are spilled across the pages of British history, we are forced to confront the atrocities carried out in his name across Afghanistan, Abyssinia, India and South Africa.

The bust of Roberts during its unveiling in 2015

In the back hall of the Bishop’s Palace a bust of Roberts stands between two commemorative plates – one of which features his face and the other features the Pope. The plate was owned by a Waterford family and was made in honour of a hero of the city who had ‘made it big’ so to speak. The bust was presented to the museum in 2015 by the Irish Guards, an order created in 1900 to mark the Irish contribution to the Boer War, and was cast from the bust which has stood in their headquarters for decades. Like many statues at the moment the presence of the bust has led to some healthy questioning and debate around Roberts and how he should be viewed today. History is a complex thing, and it is possible to learn from history without celebrating it. Roberts was extremely important to the people of Waterford in his day and at the same point was a deeply unpopular figure in the countries which felt the full might of his forces. This is why museums are the perfect location to explore the lives of controversial figures like Roberts where his military endeavours can be openly discussed and debated. We cannot ignore the history which makes us uncomfortable simply because it is easier to do so and while Roberts’ deeds are deeply unpleasant to learn about now, he is a product of his time and to ignore what happened is to invalidate the struggles and suffering of those he encountered in Afghanistan, India, Abyssinia and South Africa. Roberts stands in the hall of the building which made his great-grandfather’s career, surrounded by portraits and artefacts belonging to his family and there he remains, a complex, nuanced, grey human being.